by Chris Abbott | Sep 29, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Conflict and security

Last week the leaders of the US, UK and France made public the discovery of a second, secret, Iranian enrichment facility near Qom.

However, this was not a new find: American, British and French intelligence agencies are believed to have known about it for over two years (though only concluded that it was an enrichment plant earlier this summer). Days earlier, when it seems they realised it had been discovered, Iran attempted to head-off international criticism by declaring a “pilot plant” at Qom to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which is already monitoring the facility in Natanz the Iranians were forced to acknowledge in 2002.

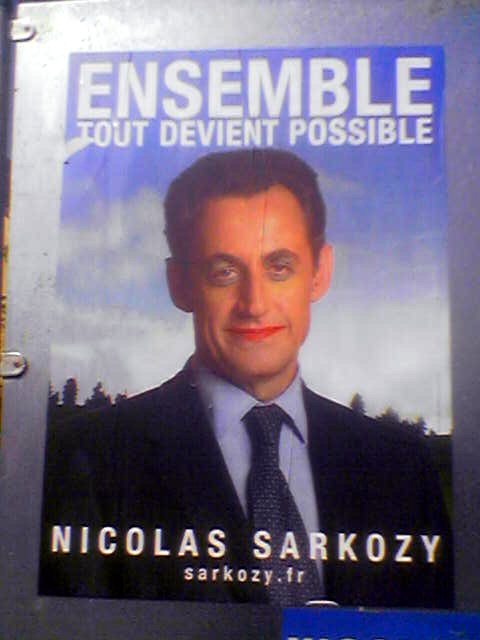

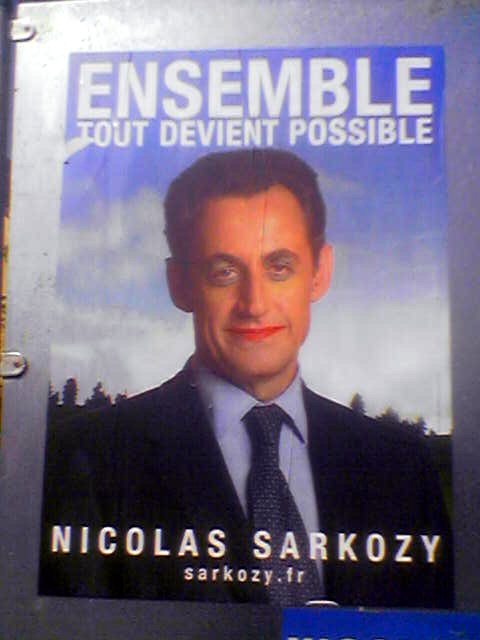

This was a propaganda gift for opponents of the Iranian nuclear programme. It allowed Presidents Obama and Sarkozy and Prime Minister Brown to make the extraordinary joint statement during an important period in the international political calendar – ahead of the G20 Summit in Pittsburgh, and days after the opening of the UN General Assembly and less than a week before the UN special session on nuclear proliferation on Thursday.

It seemed to make little difference that the three leaders represented countries with their own nuclear weapon programmes (an irony not lost on everyone).

Reactions from within the region have been understandably mixed. Iran’s Arab neighbours, particularly Saudi Arabia, fear the possibility of an Iranian nuclear weapon capability but also worry that recent developments will be the precursor to the agreement of a ‘grand bargain’ between Iran and the west that will leave Iran unchecked as a powerful regional player.

Israel – who has long been preparing for air strikes against Iran – sees the revelation that Iran has once again been misleading the international community as a vindication of its hard-line stance. The Iranian leadership itself, however, remains defiant – insisting its nuclear programme is entirely peaceful and well within the limits of international law. The Iranians view the capacity to produce nuclear power as a sign of modernity and in keeping with their position as a powerful regional actor.

Analysts will now look at what is known about the facility in Qom to try and discern if it was for use in a civilian programme as the Iranians claim. At the moment, the evidence does not look favourable. The facility is reportedly of a size to accommodate 3,000 centrifuges – too large to be a pilot plant and far too small to be of any real use in a nuclear power programme. However, this number of centrifuges can produce enough enriched uranium each year for use in a nuclear weapon if so desired (once further processed to high enriched uranium).

Ultimately, though, it is the continued deception by the Iranian regime that will raise the greatest suspicion, even amongst those that, post-Iraq, do not entirely trust the word of western governments and their intelligence agencies.

So are we a step closer to war with Iran?

Probably not. Though the war drums will beat a little louder in some capitals, not least Jerusalem, the disastrous consequences of a military strike against Iran make it unlikely, though not impossible, at this stage. But in this high risk game of international political poker the stakes have just been raised; the horse trading to follow will reveal who holds the best cards.

by Michael Harvey | Sep 24, 2009 | Cooperation and coherence, Economics and development, Global system

As the spotlight shifts from the UN General Assembly and world leaders converge on Pittsburgh for the G20, there’s been much debate about the prospects for success and the competing agendas of member countries.

– The core negotiations seem set to finalise agreement over a “framework for balanced and sustainable growth” – particularly critical from US and Chinese perspectives – that seeks to give the IMF a greater reporting role in policing global imbalances. The FT’s Money Supply blog offers a sceptical comparison of the leaked draft agreement with the IMF’s current role.

– As to the Europeans: Gordon Brown seems to be adopting a broader focus, calling in an NYT op-ed for “a new system of governance” to form the “next common economic goal”. (He also announced that UK Business Minister Shriti Vadera would be going on secondment to the South Korean government to help develop proposals on global financial architecture ahead of their G20 presidency next year.) For Angela Merkel, the “most important subject” is financial regulation; she argues that “we must not search for substitute issues”; and for Sarkozy too, the top priorities look to be bankers’ bonuses and agreement over capital requirements for banks.

– Trade and protectionism are sure to form another important aspect of negotiations, particularly for China and India. VoxEU takes an interesting look at trends in world trade since the November 2008 Washington Summit, highlighting how G20 states’ oft-proclaimed commitment against protectionism has been broken by member governments approximately once every three days since last year’s commitments. “No other statistic”, Simon Evenett argues, “better demonstrates the paucity of global leadership on contemporary protectionism”.

– Robert Zoellick, President of the World Bank, calls for the summit to focus on the world’s developing economies, highlighting the positive contribution they can make to the health of the global economy. Pittsburgh, he argues, can mark the advent of a more “responsible globalisation” founded on “multiple poles of growth”. Brazilian President, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, meanwhile, presents his take on the G20 grouping in the LA Times.

– Around the think tanks, finally: Brookings has an in-depth report focusing on some of the broader implications of the G20 agenda, from the protectionism issue to African and Latin American perspectives, as well as assessing the G20’s approach to climate change. The Carnegie Endowment, meanwhile, has an interesting take on Saudi Arabia’s approach to the summit, given its increasing exposure to instability in the financial markets and vulnerability to shifts in oil and food prices.

Elsewhere, Chatham House has analysis of some of the key short-term economic indicators, as well as long-term GDP forecasts – arguing that it is still to early too be coordinating exit strategies. The Canadian-based Centre for International Governance Innovation, meanwhile, takes a comprehensive look at some of the challenges facing the G20 as a forum for global economic governance, with contributions from policymakers and academics alike.

by David Steven | Sep 22, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Europe and Central Asia

Today, Ban-Ki Moon, worried by fading prospects for a climate deal at Copenhagen, will try and knock heads (of state) together at his Summit on Climate Change. Here’s the list of speakers:

H.E. Mr. Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations

Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, Chair, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

H.E. Mr. Barack Obama, President of the United States of America

H.E. Mr. Mohamed Nasheed, President of the Republic of Maldives

H.E. Mr. Hu Jintao, President of the Peoples Republic of China

H.E. Mr. Yukio Hatoyama, Prime Minister of Japan

H.E. Mr. Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda

H.E. Mr. Fredrik Reinfeldt, Prime Minister of Sweden

H.E. Mr. Óscar Arias Sánchez, President of Costa Rica

H.E. Mr. Nicolas Sarkozy, President of France

Professor Wangari Muta Maathai, Founder, Green Belt Movement, Kenya (Civil Society)

Ms. Yugratna Srivastava, Asia-Pacific UNEP/TUNZA Junior-Board representative, India, age 13 (Youth)

H.E. Mr. Tillman Joseph Thomas, Prime Minister of Grenada

H.E. Mr. Ahmad Babiker Nahar , Minister of Environment and Urban Development of Sudan

H.E. Mr. Lars Løkke Rasmussen, Prime Minister of Denmark

It’s a pretty standard list – major powers (check), regional balance (check), soon-to-be-submerged-island-state (check), boffin (check), civil society (check), token youth (check). But then you hit the European problem. The Swedes hold the Presidency and thus speak for the EU. Rasmussen is there because he’s going to shoulder a lot of the blame if Copenhagen fails to deliver. But how on earth has Nicolas Sarkozy managed to clamber onto the platform?

It beggars belief that, just when Europeans most need to speak with a single voice, the French president is – once again – giving his ego free rein. Or have I missed something?

by Alex Evans | Sep 18, 2009 | Climate and resource scarcity, Economics and development, Global system

So what should we all be watching out for at next week’s G20 summit? Let’s start with the obvious stuff.

– Expect to hear lots about bankers’ bonuses, in particular from Brown, Merkel and Sarkozy. I can’t find it in me to give a crap about this issue, but doubtless it will command saturation media coverage all week. More substantive on the banking front will be the question of whether concrete proposals are advanced for hedge fund rules or financial supervision regulation – lots of noise here, but not much specificity so far.

– We’ll also hear lots of debate about when to wind down stimulus programs – which was a big issue at the EU’s preparatory summit (continentals more hawkish, but Brown edgier about turning the taps off). Goldman Sachs’s Jim O’Neill has an op-ed in the FT this morning arguing that while co-ordination was needed for starting the stimulus off, it’s less necessary to have co-ordinated exit strategies.

– The IMF and the World Bank have been doing good advocacy about the need not to forget about low income countries. Zoellick and Strauss-Kahn are both arguing that LICs have an external financing deficit of around $59bn this year (for comparison, that’s exactly half the 2008 global aid total). On the plus side, G20 members have actually delivered the $500bn they promised the IMF – which means the Fund can front up around a third of the total needed. Strauss-Kahn is also talking about a breakthrough on IMF governance reform. (Believe it when I see it.)

– We’ll hear a lot about climate, but it’s hard to see what deal the G20 is supposed to cut (especially with Ban Ki-moon’s heads-level climate summit in New York the same week). The story the media runs with will be all about pressure on the US to do more, following Japan’s announcement of a tougher 2020 emissions target, and the EU’s long-awaited finance package. (Still, Obama ain’t the problem – the real issue here, of course, is that things don’t look great in the US Senate.)

The issue on the agenda that I’m most interested in for next week, though, is trade. First, what – if anything – will the G20 say on protectionism? For all the warm words at the London Summit in April, it’s increasingly clear that most G20 countries are in breach of their commitments – right now most notably in the case of the US, whose new tire tariffs are disastrous. Dan Drezner’s take on this is worth reading (things are “very, very scary”) – but on the other hand, Alan Beattie thinks White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel may have a crafty and ultimately beneficial political calculus in mind.

On a related note, how intriguing to see US sherpa Mike Froman talking up Pittsburgh’s chances of tackling global economic imbalances (“we hope to reach agreement on a framework for balanced growth, for agreeing on how to address the imbalances that led to this crisis and on some process for holding each other accountable”). Not what I expected – but great, if he can pull it off. That said, I found myself wondering last night: is it conceivable that this is part of a messaging strategy to defend the tire tariffs? Hollow laughs all round if so.

Finally, the issue no-one’s talking about but everyone should be: the impending return of the food / fuel price spike. All these stories about oil companies finding new giant fields are so much straw in the wind. (So the new Jubilee field off Sierra Leone has 1.8bn barrels? Great: a whole twenty-one days’ global demand. Colour me thrilled.) The more fundamental point is about demand, which is picking up again in the non-OECD economies – and let’s remember that it’s in these countries that all the demand growth for oil will come between now and 2030.

The stage remains firmly set for a renewed oil supply (and hence price) crunch in the short term – and when that happens, food prices will go straight up too, as costs for transport, fertiliser and on-farm energy use race upwards and biofuels become even more competitive as a source of demand for crops. We’re already at a baseline of 1.04bn undernourished people (compared to 850m before the last food price spike) – do the maths. So my wish list for the G20?

- $6bn funding for WFP – now.

- Leave the trade round on hold, but agree emergency WTO rules against food export restrictions (like the ones that already exist in NAFTA).

- Build up a multilaterally managed emergency food stock – maybe part real, part virtual (see Feeding of the 9 Billion for full details).

- Commit to universal access to social protection systems by (say) 2015 – and lock the funding in place, now (only 20% of the world’s people currently have access to them – but these are the best-defence resilience mechanism for poor people facing price spikes, way better than price controls or economy-wide subsidies)

- Bring China and India into full IEA membership, so that they’re part of its emergency supply management mechanism.

- Start driving real inter-agency coherence by commissioning the most important multilateral agencies for scarcity issues – UN, Bank, Fund, OCHA, WFP, FAO, IEA – to produce a joint World Resources Outlook. We need the integrated analysis; we need the political momentum it will create.

- Ask Ban Ki-moon to set up a High Level Panel to look at the international institutional dimensions of climate, scarcity and development – covering not just the UN, but the entire international system. This is the bit of international system reform that both the 2004 and 2006 High Level Panels left for another day. Today is that day.

by Michael Harvey | Sep 15, 2009 | Economics and development, Europe and Central Asia, Global system, North America, UK

– With the anniversary of Lehman Brother’s demise, the FT recalls the events of that fateful weekend last September. The NYT has reflections of three former Lehman employees, while a Guardian roundtable asks what lessons, if any, we’ve learned from the bank’s fall. Niall Ferguson, meanwhile, rails against those who argue “if only Lehman had been saved”. He suggests:

Like the executed British admiral in Voltaire’s famous phrase, Lehman had to die pour encourager les autres – to convince the other banks that they needed injections of public capital, and to convince the legislature to approve them.

– Sticking with matters financial and economic, Der Spiegel has an interview with the head of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, on the Fund’s actions during the crisis and the potential for a new role for the institution going forward. Former MPC member, David Blanchflower, meanwhile, offers a telling insight into the inner workings of the Bank of England’s decision-making as financial meltdown ensued.

– Elsewhere, the WSJ reports on President Sarkozy’s call to broaden indicators of economic performance and social progress beyond traditional GDP, following the findings of the Stiglitz Commission. Richard Layard, expert on the economics of happiness, offers his take here, arguing that “[w]e desparately need a social norm in which the good of others figures more prominently in our personal goals”.

– Wolfgang Münchau, meanwhile, assesses the implications of an Irish “No” vote in the upcoming referendum on the Lisbon Treaty. “There is an intrinsic problem for the Yes campaign in Ireland”, he suggests, “which is that the core of the treaty was negotiated seven years ago. This is a pre-crisis treaty for a post-crisis world… If we had to reinvent the treaty from scratch, we would probably produce a very different text”.

– Finally, last week saw the German Marshall Fund of the US publish its Transatlantic Trends survey for 2009. Unsurprisingly, a majority of Europeans (77%) support Barack Obama’s foreign policy compared to the 2008 finding for George W. Bush (19%); though the “Obama bounce” was less keenly felt in Central and Eastern Europe than Western Europe. A multitude of other interesting stats – on attitudes to Russia, Afghanistan, Iran, the economic crisis, and climate change – can be found here (pdf).